The history of Ouranoupolis…

From Monastic Land to Tourist Village

The history of Ouranoupolis can be divided into three distinct periods: The ancient, the Byzantine and the later “modern” history. The ancient period relates to the ancient town of Ouranoupolis which gave it’s name to the present village while the Byzantine period sees the development of Mount Athos as a unique monastic state which included the land of Ouranoupolis. The later “modern” period is the story of homeless refugees from Asia Minor who found a new home at the edge of the Holy Mountain.

Very little is known about the ancient town of Ouranoupolis which gave it’s name to the present day village. It was certainly built around 300 B.C. by Alexarhos the brother of Macedonian king Kassander. The exact position of the ancient town is not known but it was certainly located on or close to Mount Athos. It was important enough to have struck it’s own coinage. Some of these coins have been found in the area and three of them are exhibited in the British Museum. They depict an eight rayed star (the sun) on one side and Aphrodite Urania seated, holding a long filleted sceptre, surmounted by a ring. Next to the sceptre there is a conical object surmounted by a star.

The representations on the coins indicate the existence of some sort of pagan cult which honoured Aphrodite, the goddess of love. The ancients thought that Alexarhos was a strange man who introduced unusual rules and strange customs to his town.

It appears that the ancient Ouranoupolis did not survive for very long. Monumental walls and possibly the remains of an ancient town have been discovered in the sea. One autumn in 1954 a Swedish underwater expedition believed to have found the remains of a town, stretching westwards from the foot of the tower towards the islands. They are said to have found the walls of houses with roads among them, a bridge and a fireplace. When they dug into the sand which covered the fireplace they found charcoals and ashes. Although this later detail cannot be confirmed there are certainly substantial walls under the sea in front of Ouranoupolis. Who is this mysterious town which seems to have been claimed by the sea? Nobody knows.

The Ancient Period

Very little is known about the ancient town of Ouranoupolis which gave it’s name to the present day village. It was certainly built around 300 B.C. by Alexarhos the brother of Macedonian king Kassander. The exact position of the ancient town is not known but it was certainly located on or close to Mount Athos. It was important enough to have struck it’s own coinage. Some of these coins have been found in the area and three of them are exhibited in the British Museum. They depict an eight rayed star (the sun) on one side and Aphrodite Urania seated, holding a long filleted scepter, surmounted by a ring. Next to the scepter there is a conical object surmounted by a star. The representations on the coins indicate the existence of some sort of pagan cult which honored Aphrodite, the goddess of love. The ancients thought that Alexarhos was a strange man who introduced unusual rules and strange customs to his town.

It appears that the ancient Ouranoupolis did not survive for very long. Monumental walls and possibly the remains of an ancient town have been discovered in the sea. One autumn in 1954 a Swedish underwater expedition believed to have found the remains of a town, stretching westwards from the foot of the tower towards the islands. They are said to have found the walls of houses with roads among them, a bridge and a fireplace. When they dug into the sand which covered the fireplace they found charcoals and ashes. Although this later detail cannot be confirmed there are certainly substantial walls under the sea in front of Ouranoupolis. Who is this mysterious town which seems to have been claimed by the sea?

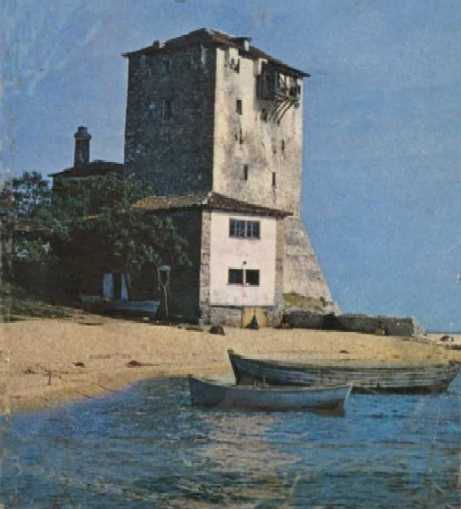

The tower of Ouranoupolis was built during the 14th century A.D., certainly before 1344. It was the principal building of the metohi (farm) of Prosforion which belonged to the important monastery of Vatopedi. In May 1379 the ruler of Thessaloniki Ioannis Palaeologos stayed in the tower and issued various concessions in favour of Mount Athos. He removed the obligation for the metohi (farm) around the tower to pay any tax and the original document is still kept at the monastery of Vatopedi. The farm prospered and expanded, taking over all the land in the area, including that of the monastery of Zygou which had declined by then. The tower was used as the living quarters of the monks managers of the metohi (farm) until 1922. It was set on fire in 1821 but was repaired some time after 1865 when a few other buildings around it were added. Those were an olive press with a water well, an oven, stables, an iron monger’s workshop and two large houses where the civilian workers lived. Today only the tower, the iron monger’s workshop and the worker’s houses survive.

The Resent Period

Since the ancient times Greek populations lived not only along the coast of Asia Minor but deep inside it. Large Greek communities lived in Constandinopol and in Smyrna. Whole Greek villages existed on the Princes Islands in the Propontis and in Caesarea deep into Turkey. Most of them kept their Greek language and their Greek Orthodox religion, living in relative prosperity in concord with the Turkish populations. That ended in 1914 when the Turkish army started a whole scale persecution and deportation of the Greek populations in Turkey.

An ill fated Greek military expedition against Turkey in 1921 ended in disaster and offered an excuse to the Turks to start a systematic genocide of all the Greeks living in Turkey. The League of Nations intervened and devised a plan to exchange the Greek populations living in Turkey with the Turks living in Greece. Whole villages were uprooted, took with them whatever they could carry and boarded boats and trains bound for mainland Greece. Smyrna, a prosperous city with a large Greek population was burned to the ground and most of the Greek inhabitants were killed. Greece was presented with the problem of housing half a million destitute and traumatized people. Initially the refugees were taken to various holding areas from which they were dispatched to every corner of Greece to start a new life.

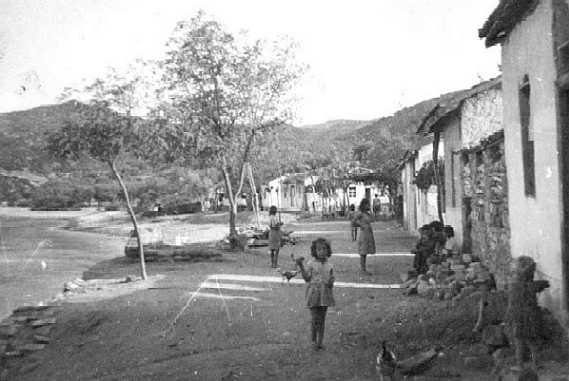

As a solution to the problem the Greek government decided to confiscate the monastic land around the tower of Ouranoupolis and use it to settle some of the destitute refugees. The monks promptly left the area and one day in 1922 the first boatload of refugees arrived. They were from Caesarea, former merchants and carpet wavers. They initially moved into the abandoned monastic buildings and used them as communal living quarters until the first houses were built. More refugees arrived every subsequent year until 1928 and gradually a small village of 90 cottages was formed. Those later refugees were from the Princes Islands in the Propondis, former prosperous fishermen.

The village was initially named Prosforion and was attached to the town of Ierissos. In 1946 the name was changed to Ouranoupolis, a reference to the ancient town and it became a village in it’s own right. The first refugee houses, white-washed, red tiled, one bedroom single story houses with small gardens were built by a German contractor.

To help the refugees each family was given a cottage, a plot of land to cultivate, some olive trees and ten sheep which died soon after from starvation and were replaced by more resolute goats. Fishermen were given a grant to buy a boat. Living was harsh because water was scarce and the dry land produced very little. The only available source of employment was Mount Athos. Men disappeared into the monasteries for many months where they worked as labourers, struggling to provide for their families.

It was a harsh place for anyone to settle in, more suited to monasticism than the establishment of a village. The waterless land was decaying granite, heavily covered with thick, thorny scrub. The place was isolated from the rest of the world, the only contact being the monks of Mount Athos.

There was no road by land, but a mule track followed a winding course through the mountains of Halkidiki as far as Tripiti, 9 Kilometres away from Ouranoupolis. After that one either walked or took to a sailing boat for the final leg of the journey. An ancient edict prohibited the construction of a road “on which a wheel could run” to Mount Athos and therefore Ouranoupolis remained without a road, isolated for many years. In 1959, after a particularly harsh winter the villagers, led by their president Ioannis Tozakoglou, took spades and shovels and constructed a dirt track, the first road to the village. A British Land Rover was the first car to reach the village. Soon after the road was improved and a daily bus service was established. This brought the first tourists a trend that gradually lifted the village out of poverty and into a more prosperous future as a tourist resort.

Now a days the loud speakers outside the tavernas blurt out modern music. From the sea comes the sound of outboard motors, the sailing boats of the old days gone. But when the evening comes and the fishing boats light their stern lights the passage of time is forgotten. The natural beauty and feeling of tradition overcome the modern trends, especially for the visitor who takes a stroll through the olive groves and the winding paths on the hills.